AI vs. History

Navigating the wild wild west.

We recently did an episode called AI vs. the Founders about a frustrating personal experience I had with AI that speaks to a wider problem.

Here’s what happened: I shared a quote from Thomas Jefferson on the Plodding Facebook page, and a reader commented saying AI told her it wasn’t a genuine Jefferson quote.

Look, I’m used to computers not believing I’m human just because I can’t identify every single picture with a bicycle in it, but it’s a strange feeling to have a robot call you a liar. I knew the quote was 100% legit, and that I’d found it on the National Archives’ Founders Online site, so I went to the site to prove the quote was genuine, but the site wasn’t loading. Why wasn’t it loading, you ask?

Because content-scraping AI bots had overloaded it with crippling traffic.

For those keeping track at home, artificial intelligence was effectively distorting the truth about the past and blocking access to it. The nerve.

Since that episode dropped, I’m happy to report there has been one piece of good news: The Senate removed the bizarre provision in the One Big Beautiful Bill that would prevent states from regulating AI for 10 years. Sadly, that’s the only good news. We’re still facing the defunding of efforts to preserve and share historical resources, and AI bots are still bringing down historical archives.

It turns out these attacks have been going on for a while, and they’re not stopping. Recently, the Hagley Digital Archives, a tremendous resource for many researchers, was temporarily taken offline with this explanatory note:

“The Hagley Digital Archives is currently offline due to a sustained bot attack. Our support team reports that ‘bots have accelerated to levels not previously seen,’ as AI systems increasingly target sites like ours to train machine learning models.”

There are rules in place to prevent this kind of bot traffic from affecting websites, but new or irresponsible AI companies appear to be ignoring them. They’re indexing pages that shouldn’t be indexed, and overloading sites in unscrupulous ways. This irresponsible behavior needs to be prohibited, but regulation and enforcement are few and far between because we’re still in the early, wild wild west days of AI.

When I see Google’s AI-generated responses at the top of search results, there’s a disclaimer: “AI responses may include mistakes.” It reminds me of the warning on pool toys: “This is not a lifesaving device.” The problem is we’re relying on AI for a lot more than fun in the sun.

Here’s one example of the expansion of AI can affect people’s money and health: this administration just announced that with AI, it will be auditing far more Medicare payments than ever before—after implementing largescale layoffs to its staff. Don’t get me wrong, I believe public and private partnerships to build things and increase efficiency are essential. But because this is the wild west, I’m leery about deputizing robots to evaluate complex mistakes when the robots are prone to even greater mistakes and can’t be held accountable.

I can’t fully trust AI to give me accurate information about John Adams, and we’re entrusting it with a whole lot more.

The fact is that AI isn’t going away, and we need to find a way to integrate it better than we are now. Because it’s making us dumber. A recent study showed that subjects who used AI to write papers—as opposed to search engines or their own brains—used fewer parts of their brain, created similar and less creative work, and demonstrated less understanding and ownership over their work.

So what can we do about it?

The New York Times’ David Brooks has an interesting suggestion for combatting the overuse of AI: shame. He concludes his essay by saying, “It would be nice if there were more stigma and more shame attached to the many ways it’s possible to use A.I. to think less.” It would be nice, wouldn’t it? But is it practical? Stigma and shame might have worked to keep people in check in the honor-based society of George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, where your reputation was everything and lying had consequences. I’m not so sure of the stigma and shame’s place in our world.

And, as with most things, I’m part of the problem. I admit it. I believe there is an appropriate role for AI generated art. Specifically ridiculous historical AI art, like the cover art for our latest podcast episode:

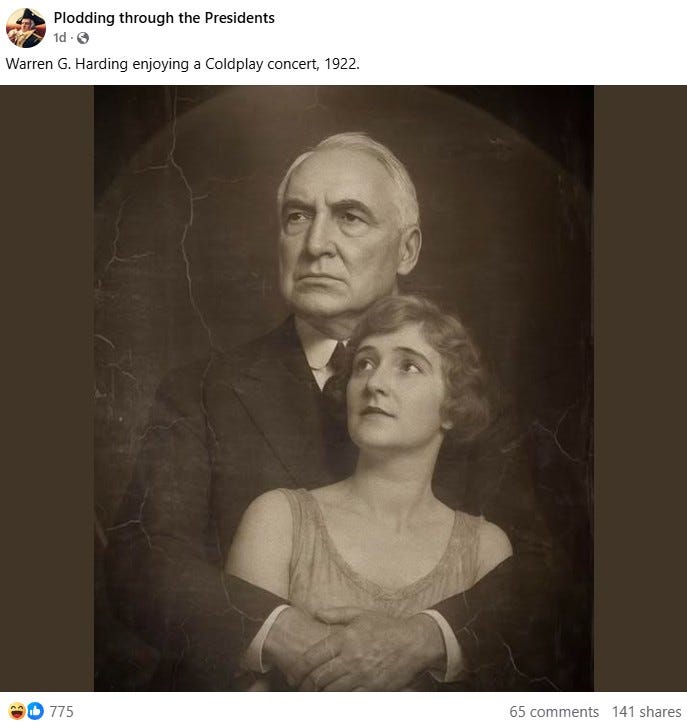

And the image I created for this timely, esoteric Facebook post:

The truth is that I don’t have the time or money to commission artists to bring these weird visions to life, and I don’t feel much shame in sharing them because of the joy they create.

I also don’t have the answer to the future of AI and its impact on history and the world, but I’d like to think it might lie with a mix of regulation, restraint, and reproach. And more than a little ridiculousness.